About Me

The Manifesto

The Further Adventures of Hiatus

This hiatus just got REAL

Meh declared cromulent

The usual post-election vocab lesson

Contest FAIL

A National Punctuation Day Contest

No one will ever pick up on this hyperbole

A spirited defense of good grammar

Good Stuff: 8/29/08

Montreal: phonetics, purists, and even some terror...

Back to Main

Bartleby

Common Errors in English

Netvibes RSS Reader

Online Etymology Dictionary

Research and Documentation

The Phrase Finder

The Trouble with EM 'n EN

A Capital Idea

Arrant Pedantry

Blogslot

Bradshaw of the Future

Bremer Sprachblog

Dictionary Evangelist

Double-Tongued Dictionary

Editrix

English, Jack

Fritinancy

Futility Closet - Language

Language Hat

Language Log

Mighty Red Pen

Motivated Grammar

Omniglot

OUPblog - Lexicography

Style & Substance

The Editor's Desk

The Engine Room

Tongue-Tied

Tenser, said the Tensor

Watch Yer Language

Word Spy

You Don't Say

Dan's Webpage

Wednesday, November 5, 2008 10:10 AM

Bart: I am so sick of hearing about Lisa. Just because she's

doing a little better than me—

Marge: She's President of the United States!

Bart: President-*elect*.

Congrats to those of you who supported Obama. It's a giddy time for wonks and English geeks generally: we get to spend the next few months correcting President to the delightfully technical President-elect.

I don't see any U.S. newspapers using it, but there's an additional potential distinction, President-designate. Check out this 1976 entry from The American Political Dictionary:

Following the November popular election, the winning candidate is unofficially called the "President-designate" until the electors are able to ratify the people's choice. Under the Twentieth Amendment, the President-elect is sworn into office at noon on the twentieth day of January, and if the President-elect fails to quality at that time, the Vice President-elect then acts as President.

As Wikipedia points out, if the President-elect dies before being sworn in, then the Vice President–elect becomes President. If, however, the President-designate dies before being voted President-elect on December 15th, then the Electoral College could choose a different President-elect, and they are not required to choose the Vice President–designate.

Obviously the news outlets are just following the common usage of President-elect. For one thing, calling Obama President-designate might come off as the same sort of dog-whistle that mentioning the middle name Hussein is in some circles.

Still, odd that no copy editors have latched onto the December 15th date for "official" President-elect status; it seems like the sort of petty terminological minutia they usually enjoy.

Labels: editing, grammar politics, semantics, vocab

If you want to talk about minutiae, what about the fact that the day after the election is not always November 5th?

Ah yes! A rookie mistake on my part, not checking that date.

That's totally a word

Monday, August 4, 2008 12:02 PM

This has always bothered me. Unless you're actually talking about a string of letters that doesn't signify anything, it makes no sense to claim that something "isn't a word."

Alternatively, if you don't think that a word is "real" until it's appeared in the OED or the Official Scrabble Dictionary or the Google corpus, then I can see the sense of your argument, but I think you should know that you have an unusual definition of real.

(One that you won't find in any dictionary, I might add.)

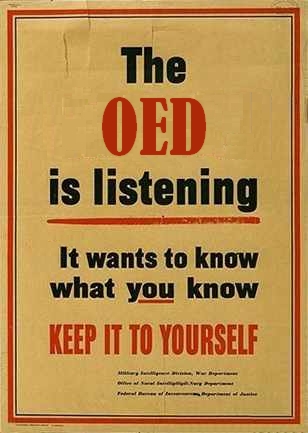

The notion that a dictionary could be the arbiter of what words are "real" fascinates me. I understand that most people adopt this mindset thoughtlessly, but it would be cool to see some prescriptivism which took it seriously.

I imagine something like this:

Anyways, I found it odd that McKean took such a diplomatic stance, focusing on speakers uncertain of their own words when — as any good Grammar Warrior knows — claims that such-and-such "isn't a word" abound in pop-prescriptivism.

I could find examples elsewhere, but I'm going to pick on the folks at Everything Language and Grammar because they're professionals.

Excerpts:

"Gonna is not a word; it's merely a verbal laziness of going to." [cite]

"I use ain't as an example because we should all know that it's not a word" [cite]

"As I like to say, irregardless is not a word regardless of its presence in the dictionary—period." [cite]

What they're really talking about here is whether a word is acceptable or appropriate or cromulent — not whether or not it's "a word, period." Frankly, this is sloppy writing, because I don't have any idea what "word" means here now. I don't think that they're trying to pretend to authority and rigor that their prescriptivism doesn't have, but I can't be certain.

In contrast, the post on doable strikes just the right tone:

"I'm not saying that this is not a word; however, just because something is a word doesn't mean that it's necessarily the best way to express yourself."

This is aptly put. Anyone is free to make the case against any word as a matter of taste — in fact, we did this just the other day at Editrix — and people might agree with you that this word is ugly because it mixes Latin and Greek or that that word is pointless because we already have a better one for the same thing or that my good friend irregardless is stupid because it has a redundant affix.

However. If you want to actually dismiss certain words as non-words, turn "I don't like that" into "that's wrong" — well, then I want a definition of real word that makes sense. And I want something deontological, so that I can figure out if a word is "real" even when you're not around.

Labels: grammar politics, semantics

I like to tell peevologists that the ir- in irregardless is not a negative prefix but an augmentative one just like the in- in inflammable. (I mean, can you prove it ain't?) They don't even blink.

Playing a game of chicken with folk etymology... yes, this just might be the thrill I've been looking for.

It may be that ir-regard-less (dashes added for emphasis) has a valid separate meaning, in that negating a negation is cumbersome, but within the confines of debate sometimes philosophically valid. You negate my regard for a given concept (regardless) and I find that your negation is invalid, and negligible, so irregardless your specious argument, I continue to assert my position.

It is cumbersome English, but not illegal or illogical.

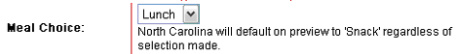

Wundergrammar: A North Carolina rule

Monday, July 14, 2008 7:21 PM

I'm guessing that this prescription has more to do with financial and/or legal considerations than with matters grammatical, but I'm still baffled.

Why not lunch? Or dinner, for that matter? Do the good people of North Carolina not deserve a proper meal?

Labels: semantics, wundergrammar

In defense of the humble ecdysiast

Monday, June 23, 2008 4:32 PM

You need to be honest with yourself. Go outside and find a locked car — or go to the back alley where missile launchers hover in a glowing light waiting for you to pick them up, or go drive down that street in your town where all the strippers hang out waiting for you to pick them up — and see if you're tempted.

As someone who's finished GTA IV and who loved the game, I'll pause here to note that weapons no longer "hover" in this installment.

Nor do I recognize the mission scenario ("an epic shootout involving missile launchers and strippers") in the essay's lede.

Nor do I remember facing off against any of the "vigilante strippers" that the author alludes to elsewhere.

It would be nice if writers concerned with dispelling myths about GTA IV could refrain from creating their own misinformation; these distortions in particular are especially irritating because they make GTA look cartoonish, which it (mostly) isn't. This game has humor and satire, but it also has drama, verisimilitude, and (fantastic) characterization. It would help if its defenders could take it a bit more seriously.

So. As you may have guessed, I want to talk about the strippers. We all know what strippers are, right?

Certainly you'd expect Bill Blake, who, even if he hasn't played GTA IV, is nevertheless an adult and (this is what's known as the "kicker") a doctoral student in cultural studies, to be aware of this phenomenon.

[...] or go drive down that street in your town where all the strippers hang out waiting for you to pick them up [...]

Neither in real life nor in the game do strippers hang around on the street, waiting for people to pick them up. To put it simply:

Stripper ≠ prostitute

I don't understand how a copy editor — or any alert reader — could miss this. Say what you will about my dubious morals (or worse, my prescriptivism), but stripper is a fairly basic term, wrongly applied here, and I'm shocked that it made it to publication.

Roughly equal to 50 brownie points

Wednesday, June 4, 2008 10:34 AM

This slang sense of solid goes back at least to the '70s. However — perhaps this is just my own personal idiolect, but I'm somewhat surprised to find that almost no definition of solid mentions that it's necessarily a substantial favor.

You could say, "Would you do me a favor and pass the mustard," but you would never call that a solid. At least I wouldn't. It would cheapen the solid.

(Obligatory Simpsons linguistic tie-in: at the end of "Bonfire of the Manatees," Homer says he can take a few days off work because "I've got a friend who owes me a solid." The next scene — wherein a manatee poses as Homer — is priceless.)

Probably of no great interest to you, but I've never heard 'solid' to mean 'favour' (of any description) in my life. Has it crossed the Atlantic? Dunno. But it hasn't reached me. Must have missed that Simpsons episode...

A $25 difference

Monday, May 19, 2008 2:43 PM

The American Heritage Dictionary defines crosswalk as

A path marked off on a street to indicate where pedestrians should cross.

Minnesota statute 169.01.37 defines crosswalk as

(1) that portion of a roadway ordinarily included with the prolongation or connection of the lateral lines of sidewalks at intersections; (2) any portion of a roadway distinctly indicated for pedestrian crossing by lines or other markings on the surface.

These warring definitions wouldn't be a problem if not for Minnesota statute 169.34.a.6, which proscribes parking within 20 feet of a crosswalk — marked or unmarked — at an intersection.

Labels: semantics

Everything now officially a blog

Wednesday, May 14, 2008 4:35 PM

Internet jargon; if used, explain that it means 'Web log' or 'Web journal'

There. There is it, the stylebook entry that the AP removed several years ago, when blog "become so common and so much a part of the language that it was no longer necessary."

The distinction between "blog means Web log" (true) and "blog is short for Web log" (untrue) is a subtle one, I get it. Maybe, if the AP entry had been a little more clear, copy editors would be going after that phony etymology like so many improper uses of the word podium.

What I don't understand is why here, now, in May of 2008, you're all using blog like some sort of catch-all for "anything written on the Internet."

(See that capitalized Internet? I did that for you. I'm sorry that I seem so angry right now.)

I've seen this many times before, but here's the lede that set me off today:

Burger King said Tuesday it fired two employees following the disclosure that an executive secretly posted blogs slamming a farmworker advocacy group.

The rest of the story ("Burger King fires 2 after blog controversy") doesn't mention blogs, just postings. Which is appropriate, because blogs were not involved in any way. It turns out that all the statements in question were made in comment threads.

Bloggerheads has a great roundup of what probably happened. Misusing blog is bad enough, but here are some useful words that should have been in the AP piece: comment, sock-puppeting, YouTube.

So how do you spot a blog? Definitions vary, but nowadays it's almost universally accepted that on a blog, content will be arranged in reverse-chronological order, i.e. with new stuff at the top. For much, much more on defining the weblog, check out my increasingly outdated master's thesis.

Or, here's a neat trick: substitute Web log for blog in your article. If you can't, you're probably misusing the word blog.

I feel perfectly comfortable being pedantic about the use of "blog." People do not write blogs; they write blog posts or blog entries. I have a feeling this is going to turn into a losing battle pretty quickly, though.

Oof. Yeah, the "individual blog posts are not blogs" battle is not going well, not at all. We have to win "comments and forum posts aren't blogs" before we can even advance to that area of the battlefield.

I wonder if the next, tech-savvy generation of editors will do a better job with this.

Dan's new word crush

Saturday, May 10, 2008 12:13 PM

golden eye - someone who can notice very slight differences in picture quality

A quick search brings up this cite from an article on Comcast's switch to 3-to-1 HD compression:

"The testers are our engineers who we call 'golden eyes,' who have a proven track record of picking up subtle differences in picture quality," he said.

The reference is probably to the animal kingdom or the monetary value of good eyesight, and not to Perrin from the interminable Wheel of Time series.

I like golden eye — it has a narrower sense than eagle eye and it pushes back against the conflation of enthusiasm and perceptual ability that you sometimes get with videophile. And this is pretty cool:

golden eye : sight :: super taster : taste.

Now I just wish we had a similar term for people who can hear all the beeps.

Cluster and Mother

Tuesday, April 15, 2008 12:36 PM

Urban Dictionary has these clippings covered.

Pause to note that these aren't merely interrupted swears, like the mother- in the new Die Hard trailer or the holy- (for holy s***) that you see sometimes in movies or Homer Simpson's epic f- in "Who Shot Mr. Burns." You can use mother and cluster prettymuch anywhere in a sentence without adding an extra pause afterwards. (Disclaimer: Our Bold Hero is not a linguist.)

No, these are abbreviations of swear words, just like F, that ubiquitous signpost for f***.

(I suppose that suck, as in you suck or that sucks, is also similar, but those phrases leave considerably more up to the imagination. Donkeys are sometimes involved! The expression this blows works the same way — goats! — although it supposedly does not have a vulgar origin.)

In some ways mother and cluster are like minced oaths (Jebus, sugar, frak, etc.), which generally derive their meaning from their resemblance to an existing profanity. However, the connection here is stronger, because mother and cluster are also the building blocks of their dirty cousins. In mothertrucker, you've got a minced oath, but in mother it's just been chopped.

Then there's this item about "clustered nuns":

http://grammatically.blogspot.com/2008/04/hail-mary-full-of-grapes.html

I suppose the abbess would be a "clustered mother."

Why is it that when some nuns are left in darkness, they will seek out the light? Why is it that when nuns are stored in an empty space, they will group together, rather than stand alone?

Explication of the Nerds

Friday, January 11, 2008 2:54 PM

If that's incorrect... well, I make no apologies when I can't Search Inside!

It's a bit silly to quibble over the meaning of terms that come to us as reclaimed insults — that is to say, via people who really don't care whether they call you a geek or a nerd or a dork — but this definition goes against what I've (almost certainly naively) understood as a commonly-held distinction between nerds and geeks.

That would be something like what you get at the end of the Nerd? Geek? or Dork? Test:

A Nerd is someone who is passionate about learning/being smart/academia.

A Geek is someone who is passionate about some particular area or subject, often an obscure or difficult one.

A Dork is someone who has difficulty with common social expectations/interactions.

I consider myself mainly a geek (that is, an English geek), but I score high in all three categories. Of the three terms, only dork seems negative to me anymore. Geeky is, of course, the new cool.

(Related: In his neo-fantasist gamer novel Lucky Wander Boy, D.B. Weiss offers an eloquent albeit chauvinist definition of geek: "A geek is a person, male or female, with an abiding, obsessive, self-effacing, even self-destroying love for something besides status." He's also very critical of faux-geek chic, a.k.a. dorkface.)

There are different schools of thought on this — for example, some people think that a nerd is just a dorky geek — but Dr. Anderegg's purported definition struck me as especially unusual.

Also: since this is a book about nerds, a few of the reviewers decide to repeat the claim that Dr. Seuss coined the word nerd in 1950.

Here's the Washington Post:

(It should be noted that another literary icon actually coined the word nerd, which first appeared in 1950 in the completely irrelevant, and typically fantastic, context of Dr. Seuss's "If I Ran the Zoo": "And then, just to show them, I'll sail to Ka-Troo, and bring back an IT-KUTCH, a PREEP, and a PROO, a NERKLE, a NERD, and a SEERSUCKER, too.")

And here's the Economist:

How very unfortunate that Dr Seuss, whose verbal pyrotechnics have given so much pleasure to so many children, should also have given them, however innocently, the ghastly label "nerd".

It's certainly the first published occurrence of the term discovered so far, but some people, including Our Bold Hero, think that the connection between the two nerds is mere happenstance, and that Seuss' word was another whimsical one-off that went nowhere.

The website The Origin of the Nerd has the low-down on this etymological controversy, but right now the earliest citation for nerd outside of Dr. Seuss is from 1951. I doubt that I'm the only would-be antedater for whom this word has become something of a white whale.

Relieved to say I scored "pure nerd."

What's up with "dork"? -- it's the only one of the three that doesn't emphasize some kind of intellectual ability. Makes them sound . . . unfortunate.

The Annual Statement from the Association of Easily Confused Englishmen

Wednesday, December 12, 2007 4:22 PM

The winner this year is some former English soccer manager I've never heard of. His "baffling" quote?

"He is inexperienced, but he's experienced in terms of what he's been through."

I'll leave it to British soccer fans to decide whether this statement holds true, but my immediate and only interpretation of this out-of-context quote is that Wayne Rooney has two types of experience, and that McClaren is contrasting, for example, the time Rooney has spent playing professionally with what Rooney has accomplished in that time.

Even if this statement is a bit clunky — well, it's hardly the worst thing they could have found. See also: 2002 and 2003.

Still, judging from the press this is getting, the Plain English Campaign is having great success pretending to be very dense.

As Ray once said of The Cure: "They are really silly people! Stop listening to them!"

Labels: grammar politics, semantics

Wundergrammar: "Brand strong"

Tuesday, November 27, 2007 4:26 PM

This striking, brand strong card is great for quick, friendly communication. 5 1/2" x 4 1/4" folded. Envelopes included.

Labels: dialect, semantics, wundergrammar

The King is Wack

Friday, November 23, 2007 12:05 PM

(That's my reality show night: has anyone else noticed the growing prevalence of Tyra Banks' pet adjective, fierce? I heard it on Project Runway.)

As you'd expect given Corporate America's current infatuation with language play, this B.K. had some very odd signs.

First, breaking news: our nation's top engineers have finally invented the Frypod.

(Photo by Hawaii)

Other bloggers have wondered if Apple can sue Burger King for leeching off its cred — I'm guessing the answer is no. For my part, I'm just amazed at what seems like an excessive amount of promotion for a new shape of fry carton.

(Also, in 2007 the iPod is no longer the hip new thing: it's an institution. There's nothing fresh about the word frypod.)

As a Minnesotan, I found another ad far more irritating. The first sign in this set says "This burger is stocked full of good stuff." The second says "Just like our 10,000 lakes."

Our 10,000 lakes, Burger King? You are a corporation from Florida, worldwide maybe but not Minnesotan. Multinational fast food chains aren't local just because they're found locally. I feel like the King is sidling up to me in a bar, asking for a favor, all calling me buddy and pal.

Fierce is one of my fave Tyra words! She uses it on America's Next Top Model all the time -- I have no idea what it means but the models all seem to know exactly what to do. Secret language?

They must be working on some level we can't understand... that would also explain Tyra's ability to demonstrate what to do and what not to do with what sometimes look like identical gestures.

[snort] I think it has to do with the number of times she blinks.

ps: we got a nice mention on Mr. Verb today if you didn't see it yet.

Never mind the lakes, I'm not sure I'd want a burger that was 'stocked full' of anything. Just doesn't sound very appetising (like eating something that was 'assembled', or 'manufactured').

Oh, and the Mr Verb mention was a result of me pimping myself out for publicity...

And you're both welcome...

Thank you, JD, for our submentions to your mention :-)

Well-pimped J.D. — and we're complementary goods! I feel like one of those fancy condoms from Pretty Woman.

I like your point about "stocked full" — it is oddly artificial. I wonder if the other state-specific advertisements are as strained.

Now, I'm just a simple Midwestern proofreader, but...

Tuesday, October 23, 2007 12:09 PM

Example:

She was mortified, and I=pissed: High-minded citizen journalism, it seems, can also involve insulting people's ethnic backgrounds.

Does the equals sign work in the past tense? Whatever. Vanessa Grigoriadis is referring to this entry, which makes no reference whatsoever to her ethnic background. Citizen journalism, it seems, can also involve jokes readers make in the comment section.

Grigoriadis isn't the first person to have done this, but I find criticizing a blog for its comments extremely dubious. As expected, the Gawker legal page includes the caveat "Gawker is not responsible for the content of user comments."

Worse still is the phony timeline Grigoriadis uses to drum up sympathy: this could have been fact-checked in about thirty seconds.

She starts by writing that

I woke up the day after my wedding to find that Gawker had written about me.

Timestamp on the New York Times wedding announcement: September 24. The announcement itself says that she was married "yesterday," which would put the actual wedding on September 23rd, a Saturday. The Gawker article was posted the following Monday, the 25th, so I'm sure the day after Grigoriadis's wedding was just wonderful.

Need more pathos? How about this:

Plus, only pansies get upset about Gawker, and no real journalist considers himself a pansy. But there is a cost to this way of thinking, a cost that can be as high as getting mocked on your wedding day.

Yeah, that must've sucked. Except: no! Because it never happened!

Names and dates, people: if Grigoriadis says Gawker hates her, check it out.

(Incidentally, what's with writing "New York Magazine"? Either magazine is part of the name or it's not.)

Rachaelisms

Monday, October 8, 2007 1:25 PM

If you've never heard of Rachael Ray — a noteworthy achievement these days — she's the goofy, unabashedly unsophisticated host of several Food Network shows. As Slate notes, she's also quite possibly "the world's most reviled chef."

Since I myself have a mild case of Rachael Ray Derangement Syndrome (full disclosure: I heart A.B.), until yesterday I'd avoided her shows.

So I didn't know.

I'm here today to talk to you about Rachael Rayisms, or as they're more commonly known, Rachaelisms (alternate spelling: Rachael-isms). These are words and catchphrases either invented or frequently used by Rachael Ray.

The most famous Rachaelism is EVOO (an acronym for Extra Virgin Olive Oil, pronounced "e-voe"). As any professional linguist could tell you, this officially became a real word earlier this year, when it was included in the Oxford American College Dictionary.

Here's Ray accepting a certificate from Erin McKean, quite possibly the world's most beloved lexicographer.

It's actually pretty cool that such a well-known chef plays with language like Ray does, and I really have to respect her for not letting the haters ruin her fun. Coin on, Rachael Ray.

I just dislike the words she comes up with. In the episode we watched, she coined the word choup, a blend of chowder and soup. Then she proceeded to say "choup" about fifty times as she made what was (in my lexicon) clearly just soup. I'm sure that for some people, even chowder is just a kind of soup.

Your definitions, like Rachael's, may vary.

Some notable Rachaelisms

Choup - A blend of chowder and soup.

Delish - A clipping of "delicious."

Easy-peasy - Easy

EVOO - Extra Virgin Olive Oil

G.B. - Garbage Bowl

Igidator - Refrigerator

Motz - Mozzarella cheese

Sammie - Sandwich

Shimmy-shake - Toss (?)

Smashed potatoes - Potatoes that have been roughly mashed.

Spoonula - A blend of spoon and spatula.

Stoup - A blend of stew and soup.

Turn of the pan - A measurement used when drizzling a liquid, esp. EVOO, into the recipe. (Also, I swear I heard her use the measurement "a third of a palm." Apparently she's a big fan of eyeballing.)

Yum-O ! - Yummy, possibly very yummy.

Rediscovering an idiom

Friday, August 31, 2007 2:22 PM

Where I was shocked to discover that Ich verstehe nur Bahnhof — German for "I only understand train station" — is a popular expression.

It's their version of "It's all Greek to me." I've been using it for years, but my high school German teacher introduced it to us as a joke, not an idiom. Since I was always the one saying it (for obvious reasons), I figured it was my teacher's invention. Omniglot has a whole list of equivalent phrases in other languages.

(Yes, their saying actually does work as a joke. The Germans clearly have the better idiom.)

The trouble with hoax

Monday, August 27, 2007 1:49 PM

This tale as it appeared in McClure's Magazine was pure fiction, and was labelled as such in the magazine's table of contents. Nevertheless, huge numbers of readers were fooled by the realistic tone of the narrative and wrote both to the magazine and to the Smithsonian expressing outrage that the last mammoth had been shot. So many people wrote in that the magazine had to publish a statement in a subsequent issue explaining that "The Killing of the Mammoth" had simply been a work of fiction. Their statement read as follows:

"'The Killing of the Mammoth' by H. Tukeman was printed purely as fiction, with no idea of misleading the public, and was entitled a story in our table of contents. We doubt if any writer of realistic fiction ever had a more general and convincing proof of success."

Of course, like the so-called Boston Mooninite Hoax, this wasn't a hoax at all — there was no deliberate intent to mislead.

Luckily, we have scare to describe situations where the public is panicking. So we can talk about the Mooninite Scare, the Cranberry Scare, the Chinese Sorcery Scare, etc. The word scare allows us to refer to these events without making a judgment about culpability or the degree of deception.

Journalists should use scare more often, and copy editors should add hoax to their list of suspicious things. It's an accusation.

However, scare still leaves us with a gap in the language: people can be fooled without being scared, and sometimes they fool themselves. The mammoth article I quoted above is one example of this, and today I ran across another: "Fake Al Sharpton Fools MSNBC."

An earlier version of this article quoted from a blog entry purportedly by the Rev. Al Sharpton. MSNBC.com has determined that the blog is a hoax.

Each of these situations was improperly referred to as a hoax, probably at least in part because the nominalization fooling would sound ridiculous.

I submit that we don't have a good noun for these situations, because people seem all too willing to fall back on this spurious use of hoax. What would work? I have no good suggestions, but it should be short enough for most heds and readily understandable to the average American newspaper reader.

Labels: semantics

The Perils of Contronymity

Monday, July 2, 2007 10:47 PM

Which is to say: everyone I have ever met uses factoid to mean "a brief, somewhat interesting fact." I was quite surprised to read that this is the newer, less-preferred usage. American Heritage notes that:

Similarly, factoid originally referred to a piece of information that has the appearance of being reliable or accurate, as from being repeated so often that people assume it is true. The word still has this meaning in standard usage. Seventy-three percent of the Usage Panel accepts it in the sentence It would be easy to condemn the book as a concession to the television age, as a McLuhanish melange of pictures and factoids which give the illusion of learning without the substance.

However, I'm so used to the newer meaning that I initially read even this example that way.

I can see why Read Roger is so upset by the contradictory definitions here: at least with unpacked, another contronym, you can nearly always figure out the meaning from the context.

That said, I'm fairly certain that my definition will prevail; it's the intervening confusion that's the problem.

p.s. A comment at Read Roger reminded me that I probably picked up my preferred meaning of factoid from the Simpsons episode "Homer Defined," wherein Homer's name becomes a contronym of sorts. In the first scene, Lisa refers to a USA Today-style newspaper as "a flimsy hodgepodge of pie graphs, factoids, and Larry King."

Drugs!

Wednesday, June 6, 2007 10:45 AM

Because the word drugs has come to be used as a synonym for narcotics in recent years, medicine is frequently the better word to specify that an individual is taking medication.

And here, already, we get to what I really want to talk about. More technical definitions to the contrary, narcotic has become a synonym for illegal drug. You know that the prescriptivists have lost the semantic battle when even the AP unblinkingly uses narcotics in this way. A friend of mine who was annoyed by this issue (he claims to consider only the narrow, technical definition accurate) was surprised to find that I would not side with him.

Neither my regular encyclopedia nor my dictionary mentions this broad usage, but at Wikipedia they've acknowledged it and attempted to side-step it thusly:

Many law enforcement officials in the United States inaccurately use the word "narcotic" to refer to any illegal drug or any unlawfully possessed drug. An example is referring to cannabis as a narcotic. Because the term is often used broadly, inaccurately or pejoratively outside medical contexts, most medical professionals prefer the more precise term opioid, which refers to natural, semi-synthetic and synthetic substances that behave pharmacologically like morphine, the primary active constituent of natural opium poppy.

While it's a definite extension of the original meaning, I wouldn't go so far as to call this broader usage of the word "incorrect" — there are probably more police and laypeople out there equating narcotics with illegal drugs than there are doctors and sticklers using the narrower meaning.

And I dare you to say that when you hear police narcotics unit, you actually think they have a different unit for marijuana, cocaine, meth, LSD, etc.

I mean, maybe they do, but psh.

As a copy editor, my initial instinct was to go with the sticklers, because in edited English, language is not a democracy (witness adviser in AP style). However, given that the broader meaning is common usage, I'd let narcotics stand in almost all cases and only worry about narcotic, the adjective, when it was describing a particular drug or its effects. Ninety-percent of the time, the use of narcotic/narcotics will be an issue of precision, not correctness.

P.S. Since I was unaware that this is even an issue, I can't help but find this Columbia Guide to Standard American English entry amusing:

Narcotics is the plural of the noun, and it requires a plural verb: All these narcotics are addictive, but only that narcotic has a deadly narcotic effect.

Doubtless they have such an entry for every noun.

Another look at Borrow vs. Lend

Tuesday, June 5, 2007 8:46 AM

In edited English: no, it's not allowed. The rules are irrational, but that's the game.

However, only very rarely in spoken English does the use of borrow to mean "to give someone something temporarily" create any actual confusion.

Mainly this is because it's clear from the context, but equally important is the fact that, for native speakers of English, certainly here in the Midwest if not elsewhere, the distinction between giving and receiving is never lost.

Compare:

You borrowed a toothbrush.While I should note that for me, *You borrowed a toothbrush to him is still ungrammatical, the last two forms aren't. And unlike the first sentence, they clearly signal that you is not the one getting the toothbrush, either through the use of a preposition to change the meaning of the verb, or with a good old fashioned indirect object.

You borrowed out a toothbrush.

You borrowed someone a toothbrush.

(I'm waiting for the day, a hundred years hence, when some schoolteacher chides a student with "You borrowed whom a toothbrush?")

What is usually the most convincing prescriptivist objection — that expanding the usage of one word will result in a useful distinction being lost — doesn't hold here, thanks to our good friend syntax.

Yet there will always be people out there who get annoyed at this use of borrow (my friend from New Jersey hateses its), even though they know deep down, in their Wernicke's area of Wernicke's areas, exactly what you mean.

The most they have is an aesthetic objection to what is an increasingly common usage.

They can safely be ignored.

Labels: dialect, grammar politics, semantics

And stoves will be called "kenmores"

Thursday, April 26, 2007 4:04 PM

(Aside: I've heard the such as vs. like distinction before, and have occasionally copy-edited for it rather than risk even that slight confusion. But I think it's a stylistic trade-off because such as probably sounds stilted to most people of my generation. We are Generation Like.)

For those of you not familiar with elimination-style reality shows, there's often a first challenge (usually for an award) followed by a second, more important challenge (for either a bigger reward or to avoid elimination).

On Top Chef, that first challenge is called the quickfire challenge. I had some problems with Top Chef (i.e. I couldn't taste the food), but quickfire challenge has always struck me as an unusually evocative phrase.

Recently I've noticed that like some of my friends, I've started applying that term unselfconsciously to the first challenge on any reality show. A quick web search confirms that we are not alone in this.

Over at Nerd World, the semantic broadening continues:

Quickfire challenge: what 5 things should the new Hulk movie do differently from the old Hulk movie?

Lev is not the only person doing this. The amazing thing is that even if you miss the allusion — he made it clear with a link, but others don't — this reference is probably perfectly intelligible.

I'd like to think that quickfire challenge has legs. Go neologism, go!

Weekend language-related geekiness

Monday, April 16, 2007 8:32 PM

(The process by which shoots grow from a stump or the base of a plant — something all of us have seen before — is known as suckering.)

Also this weekend, I had to teach someone the distinction between immoral and amoral.

The blowback from semantic confusion sucks. Put John Q. Poindexter on a T-shirt saying that, and I'd buy it.

Common Errors in English is brief on the amoral/immoral distinction:

"Amoral" is a rather technical word meaning "unrelated to morality." When you mean to denounce someone's behavior, call it "immoral."

For my part, I've been using the The Columbia Guide to Standard American English distinction:

Amoral (the first syllable rhymes with day), means "above, beyond, or apart from moral consideration," and "neither moral nor immoral." Immoral means "not in conformity with the moral code of behavior, not moral."

Because I'm for the most part an idealistic shoot-self-in-foot deontologist, I'd be offended if someone seriously called me amoral. And although I've applied the term jocularly to some of my more consequentialist friends, there are apparently enough people out there confused by the difference between immoral and amoral, or unaware that there is any difference, that both words are probably best avoided when you're not upbraiding someone.

Unless you want to do some preaching on the behalf of your personal definitions, as I did above.

For those of us crafting Standard Edited English (American), outside of quotes and editorials, I'd apply the same standard to amoral that the AP recommends for fundamentalist (under "religious affiliations"): don't use the word unless a group applies the word to itself.

Nine times out of ten, you can/should probably recast the sentence with the non-offensive secular, which (for most people, I would guess) implies a lack of religious orientation rather than the absence of moral considerations.

Think reactive, not reactionary