About Me

The Manifesto

Good Stuff: 7/31/08

DNC beers and legislative acronyms

Wundergrammar: A North Carolina rule

Good Stuff: 6/30/08

Nice-nice

In defense of the humble ecdysiast

Roughly equal to 50 brownie points

Good Stuff: 5/30/08

[sic]

A $25 difference

Back to Main

Bartleby

Common Errors in English

Netvibes RSS Reader

Online Etymology Dictionary

Research and Documentation

The Phrase Finder

The Trouble with EM 'n EN

A Capital Idea

Arrant Pedantry

Blogslot

Bradshaw of the Future

Bremer Sprachblog

Dictionary Evangelist

Double-Tongued Dictionary

Editrix

English, Jack

Fritinancy

Futility Closet - Language

Language Hat

Language Log

Mighty Red Pen

Motivated Grammar

Omniglot

OUPblog - Lexicography

Style & Substance

The Editor's Desk

The Engine Room

Tongue-Tied

Tenser, said the Tensor

Watch Yer Language

Word Spy

You Don't Say

Dan's Webpage

Monday, August 4, 2008 12:02 PM

This has always bothered me. Unless you're actually talking about a string of letters that doesn't signify anything, it makes no sense to claim that something "isn't a word."

Alternatively, if you don't think that a word is "real" until it's appeared in the OED or the Official Scrabble Dictionary or the Google corpus, then I can see the sense of your argument, but I think you should know that you have an unusual definition of real.

(One that you won't find in any dictionary, I might add.)

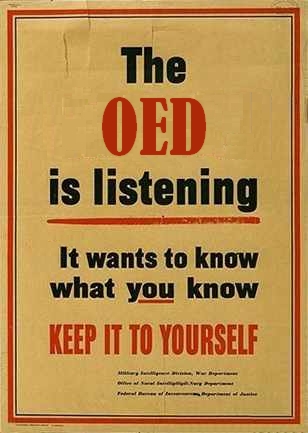

The notion that a dictionary could be the arbiter of what words are "real" fascinates me. I understand that most people adopt this mindset thoughtlessly, but it would be cool to see some prescriptivism which took it seriously.

I imagine something like this:

Anyways, I found it odd that McKean took such a diplomatic stance, focusing on speakers uncertain of their own words when — as any good Grammar Warrior knows — claims that such-and-such "isn't a word" abound in pop-prescriptivism.

I could find examples elsewhere, but I'm going to pick on the folks at Everything Language and Grammar because they're professionals.

Excerpts:

"Gonna is not a word; it's merely a verbal laziness of going to." [cite]

"I use ain't as an example because we should all know that it's not a word" [cite]

"As I like to say, irregardless is not a word regardless of its presence in the dictionary—period." [cite]

What they're really talking about here is whether a word is acceptable or appropriate or cromulent — not whether or not it's "a word, period." Frankly, this is sloppy writing, because I don't have any idea what "word" means here now. I don't think that they're trying to pretend to authority and rigor that their prescriptivism doesn't have, but I can't be certain.

In contrast, the post on doable strikes just the right tone:

"I'm not saying that this is not a word; however, just because something is a word doesn't mean that it's necessarily the best way to express yourself."

This is aptly put. Anyone is free to make the case against any word as a matter of taste — in fact, we did this just the other day at Editrix — and people might agree with you that this word is ugly because it mixes Latin and Greek or that that word is pointless because we already have a better one for the same thing or that my good friend irregardless is stupid because it has a redundant affix.

However. If you want to actually dismiss certain words as non-words, turn "I don't like that" into "that's wrong" — well, then I want a definition of real word that makes sense. And I want something deontological, so that I can figure out if a word is "real" even when you're not around.

Labels: grammar politics, semantics

I like to tell peevologists that the ir- in irregardless is not a negative prefix but an augmentative one just like the in- in inflammable. (I mean, can you prove it ain't?) They don't even blink.

zmjezhd at

August 4, 2008 6:29 PM

zmjezhd at

August 4, 2008 6:29 PM

Playing a game of chicken with folk etymology... yes, this just might be the thrill I've been looking for.

It may be that ir-regard-less (dashes added for emphasis) has a valid separate meaning, in that negating a negation is cumbersome, but within the confines of debate sometimes philosophically valid. You negate my regard for a given concept (regardless) and I find that your negation is invalid, and negligible, so irregardless your specious argument, I continue to assert my position.

It is cumbersome English, but not illegal or illogical.

Think reactive, not reactionary